Qatar cash and cows help buck Gulf boycott

June 5, 2018Deep in the desert, in an air-conditioned barn, a cow steps onto a state-of-the art, mechanical carousel to have a milking machine attached to her udder.

A year ago, Qatar had no dairy herd – relying on milk imported from Saudi Arabia. Now, Baladna farm has 10,000 cattle. Most come from top breeders in the United States.

The first cows were flown in on Qatar Airways, a month after the start of the Gulf crisis, when this tiny state was put under a land blockade by its Arab neighbours.

They have become a symbol of national pride for Qatar in its new push for self-reliance.

“Everybody said it cannot be done and we have done it,” says Peter Weltevreden who manages the farm.

“Our promise was that a year after the siege we would be self-sufficient in fresh milk.”

- What is the Qatar crisis about?

- The online war between Qatar and Saudi Arabia

- Are Qatar terrorism claims fair?

On 5 June last year, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt cut off all diplomatic, trade and transport links to Qatar.

They accused it of supporting terrorism, stirring up regional instability and seeking close ties with their arch-rival, Iran.

Qatar denied that and refused to comply with a long list of demands, including closing its Al Jazeera news network.

This wealthy emirate has since used its vast riches from offshore gas to find ways around its isolation, and sees the boycott as a challenge to its sovereignty.

“The main thing that the blockading states are aiming for [is] a power consolidation in the region,” Qatar’s Foreign Minister, Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman al-Thani, tells me.

“They started to draw the picture of terrorist on anyone who is different from them.”

Old enmity

Qatar blames the start of last year’s crisis on what it says was a cyber-attack on its state-run news agency, which published comments purportedly from the ruling emir.

He was quoted as expressing sympathy for Hezbollah militants in Lebanon and Hamas in Gaza, and claiming that Donald Trump might not last long as US president.

However, analysts say the roots of the disagreement go back much further.

“This was an issue that was kept bottled for 20 years but it just came out in the open a year ago,” says Ali Shihabi, the Saudi founder of the Washington-based, Arabia Foundation.

He refers to tapes that emerged after the fall of Libyan leader Colonel Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 which appeared to show the Qatari emir’s father plotting against Saudi royals when he was ruler.

Mr Shihabi says that Qatar reneged on agreements to stop payments to dissidents in other Arab countries and gave them a platform on Al Jazeera.

“Qatar with 300,000 citizens has taken on the 22 million citizens of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt, the biggest Arab country by far,” Mr Shihabi says.

“It is a little brother and you shouldn’t play bigger than you are, because ultimately that backfires and causes problems.”

Turning to Iran

For now, Qatar is finding ways around the land blockade.

It opened a new $7bn (£5.2nb) port on the Gulf coast, earlier than previously planned. This is helping to shield its economy from sanctions imposed by its neighbours.

The port is now being used to import building materials for the 2022 World Cup stadiums, keeping construction on track.

But Qatar is also being pushed closer to Iran – with which it shares a maritime border and its largest gas field. Qatari planes now rely on access to Iranian airspace.

“Iran is our neighbour. We have to have co-operation and communication with them,” says Mr al-Thani. “We have differences with them on policies in the region but this cannot be solved by confrontation.”

The US – which initially backed the Saudi-led side in this dispute – has recently been calling for Arab Gulf unity as it tries to build support for new sanctions against Iran.

There is a large US military airbase in Qatar.

Patriotic fervour

In Doha’s historic market, Souq Waqif, Qataris hope for an end to the blockade which has cut them off from relatives and friends from other parts of the region.

“The Gulf states are all connected through marriages,” says one man, who has a Saudi wife, now unable to visit her mother in Riyadh. “It’s painful to be separated from our families.”

However, there is defiance too and a renewed sense of patriotism.

Children in the market carry helium balloons with pictures of the young emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani. His face is displayed on car stickers, mugs, T-shirts and skyscrapers across the bay.

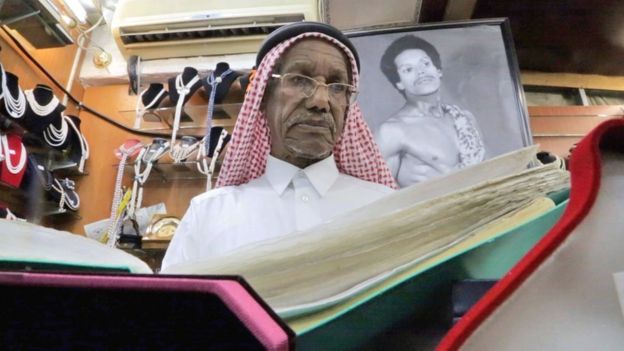

At 84, Saad Al-Jassim remembers a time long before his nation was rich. A former pearl diver, also known for his feats as a strongman, he says Qatar must stand firm.

“We are now much, much better than before. What we were going to buy from [others] we are now making it here,” he says.

“It’s my country, I love it and I know that it’s better than the others [by a] hundred times.”

This article was originally published on the following website: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-44354409

معتز الخياط , #معتزالخياط , #معتز_الخياط

Moutaz Al Khayyat, #moutazalkhayyat , #moutaz_al_khayyat